Context Widows

or, of GPUs, LPUs, and Goal Displacement

The argument about whether large language models can “do science” has the structure of a trap. The debate proceeds along predictable lines: enthusiasts point to protein folding, to materials science, to the generation of novel hypotheses; critics point to hallucination, to the absence of understanding, to the difference between pattern-matching and insight. But answer yes and you’re a booster, answer no and you’re a skeptic, and either way you’ve made the technology the protagonist. Both sides assume the only question worth asking is a capabilities question: what can these systems really “do.”

This framing has a certain intuitive appeal, but it’s the wrong question—or, more precisely, it’s a question that forecloses the more interesting ones and leads us circling around questions with no grounding in social reality. There’s a stealth neoplatonism embedded in the term “scientific discovery,” as if discoveries exist in some ideal realm waiting to be accessed—or in the video-game addled vocabulary of contemporary science policy—waiting to be “unlocked.” The debate is reduced to one about whether LLMs have the right kind of key. From a constructionist perspective—the tradition associated with Bruno Latour and science studies more broadly—this gets the epistemology backwards. Galileo’s telescope didn’t access some pre-existing truth about Jupiter’s moons; the moons became scientific facts through a process of enrollment, as the telescope’s outputs were taken up by institutions, integrated into arguments, and accepted as evidence. I’m a half-hearted Latourian at best, but on this point I’m a whole-hearted constructionist: whether LLMs can make “scientific discoveries” is no more interesting a question than whether Galileo’s telescope “really saw.”1

The better question is whether LLMs can be usefully integrated in the processes by which scientific knowledge gets made, validated, and disseminated. And here “can” doesn’t mean “will.” Despite what “tech-tree” theorists of technological change may be selling, a technology’s potential uses are not its actual uses, and its actual uses are shaped by the institutions that take it up, the problems these institutions are already trying to solve, the metrics by which they already measure success. To ask about LLMs and science is to ask what program was already running when they arrived. The program, as it turns out, had been running for decades, and it was not optimized for epistemic depth.

Something happened to the social organization of American science in the early 1960s—a shift that historians have traced through changes in language, funding structures, and self-conception. David Hollinger has noted that the phrase “scientific community” was anything but new (C.S. Peirce had used it a century earlier), but its frequency of public use increased dramatically around 1962.2 Where one formerly referred to “scientists” or “the scientist,” one now spoke of “the scientific community”—a linguistic shift that flagged a new consciousness of science as a collective enterprise amenable to management, policy, and measurement.

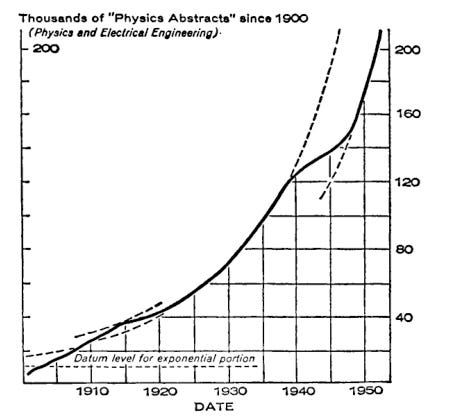

This was not merely a change in vocabulary. In the same years, a cluster of influential works made science newly visible as a system that could be studied, quantified, and administered. At the OECD, new measures were developed to measure the research outputs of entire nations, with the goal of harnessing scientific productivity in the name of economic growth. Derek de Solla Price, a physicist turned historian of science at Yale, published studies demonstrating that scientific literature had been growing exponentially since the seventeenth century—a finding that raised urgent questions about how anyone could keep up, and how institutions could identify what mattered.3 Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions reframed the history of science around paradigms and the communities that held them, making the social organization of science central to its epistemology.4 And Fritz Machlup, an economist at Princeton, began quantifying what he called “the knowledge industry,” treating the production and distribution of knowledge as an economic sector susceptible to the same analysis as manufacturing or agriculture.5 Together, these works made science legible as a system—and legibility, as James Scott has argued, is the precondition for management.6

This new legibility of science created a problem: how do you manage a system that produces more literature than anyone can read. One answer, developed through the 1960s and institutionalized in the 1970s, was citation metrics. Eugene Garfield’s Institute for Scientific Information built tools to track who cited whom, which journals mattered, which papers had influence.7 The intention was to solve an information overload problem—to help researchers find the important work in a flood of publication. This was a reasonable response to a real problem. But solutions curdle. The tools built to navigate the literature became tools to evaluate the people who produced it. Citation counts migrated from library science into hiring and promotion decisions. What had been an instrument for managing information became an instrument for managing careers.

The tools also imposed a single, uniform theory of what citation means. In different disciplines, citations do different kinds of work: in some fields they primarily transmit credit, in others they serve innumerable other functions—pointing a reader toward evidence, documenting a source, establishing that a claim can be checked. The metrics flattened this distinction into a single function: citation as credit, as endorsement, as vote. In fields where citations had primarily served evidentiary purposes, the new regime redefined the practice around a logic that had never been native to it. The measure didn’t just count citations; it reshaped what scholars understood their citations to be doing. You see this everywhere, and not only in attempts to game these metrics. This logic has begun to invade fields outside of the sciences. In my own field, history, you can see the social meaning of citation slowly being altered, probably most noticeably in calls not to reward bad people with citations. That we are attempting to target a system that doesn’t serve us, which doesn’t share our understanding of the meaning of citation, and that doesn’t actually measure the research outputs of book-driven fields doesn’t seem to matter.

Robert Merton saw this coming, though he couldn’t stop it. In 1940, long before citation indices existed, Merton had theorized the phenomenon he called “goal displacement”—the process by which instrumental values become terminal values, means transmuted into ends.8 The measure becomes the target; the proxy becomes the prize. His students built an entire subfield of organizational sociology around this insight, studying how bureaucracies drift from their stated purposes toward the optimization of whatever gets measured.

Three decades later, Merton found himself in an awkward position. By 1974, Garfield’s citation tools had become influential enough that a conference was convened at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences to assess their implications.9 Merton attended, and he warned Garfield directly: “I’d like to get on the record the problem of goal displacement as it might work with citation analysis.” But Merton didn’t only warn. He sat on ISI’s board of advisors. He gave Garfield strategic advice about how to position the company. And when Garfield worried about evaluative misuse of citation data, Merton reassured him that massive use for appointments and promotions was “not in the cards.”10 He was wrong, and some part of him knew it. A footnote in a 1972 paper Merton co-authored with Harriet Zuckerman had already conceded the problem: using citation analysis for appointments and promotions would, they wrote, “invalidate them as measures altogether.”11

The tools would change what they measured; scientists would adapt their behavior to optimize for the metrics. What Merton called “spurious emphasis on publication for its own sake” would become the norm rather than the exception.12 How could the man who theorized goal displacement fail to see it operating on himself? The anthropologist Mary Douglas, to my mind the most incisive analyst of institutions in the twentieth century, offers one answer: institutions generate the categories through which their members think, and even the most reflexive social scientist is not exempt—we are inside the systems we analyze, and the analysis does not lift us out.13 The irony of Merton’s position is structural, not personal. He was inside the institution he had diagnosed.

A common and—at this point—hopelessly clichéd response to this history is to invoke Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. The solution, in this interpretation, is to find better measures—more sophisticated metrics, altmetrics, multi-dimensional assessment. If citation counts can be gamed, supplement them with other indicators. If any single indicator can be gamed, use a portfolio. The search, as Keith Hoskin has put it, is always for “better targets.”14

But this response misses what’s actually wrong. Goodhart’s Law is a cybernetic feedback problem—the measure gets corrupted, so fix the measure. Goal displacement is a different diagnosis that is being made on a different patient. The problem is not in the metric but in the organizational form that needs metrics to function. The emphasis is inverted. Goodhart asks about the validity of the measure; Merton asks about the consequences for the thing being measured and the organization doing the measuring. One implies we should repair the instrument; the other suggests the instrument is working exactly as institutional logic requires.

Framing the dysfunction as “Goodhart’s Law” constrains what questions you can ask. It leads, inevitably, to the search for better indicators—exactly the program that metascience reformers have pursued for the past two decades through pre-registration, registered reports, open science initiatives, DORA declarations, altmetrics manifestos.15 These are not trivial interventions, and some of them may help at the margins and for a little while before the players in the game figure out how to manipulate them. But they remain inside the frame, tinkering with measures while leaving the organizational form untouched. The measures don’t just assess science; they reshape what kinds of projects researchers choose to pursue, what questions seem worth asking, what work seems worth doing.16 Fixing the metric doesn’t fix that.

Into this context—a scientific system already optimized for measurable output, already decades into goal displacement, already reshaping research priorities around metrics rather than problems—arrive large language models.

They did not arrive as disruptors. They arrived as intensifiers. LLMs function as an accelerant for the existing optimization machine, making the logic run faster rather than challenging its foundations. The technology can help write more papers, synthesize more literature reviews, produce more of the shapes that hiring committees evaluate in their twelve minutes with a file. It needn’t have been this way, or at least one can imagine it being otherwise. In a different institutional context, LLMs might be enrolled as tools for synthesis, for identifying gaps in literatures, for connecting disparate fields. Some of this happens, in local pockets, where researchers use them as tools for exploration and connection rather than production. But the dominant pattern is intensification. The technology is shaped by the logic already in place, and it makes that logic run faster.

The evidence is already accumulating. In February 2024, the journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology published a paper featuring AI-generated images of a rat with grotesquely oversized genitals and labels like “testtomcels” and “dck”; it was retracted within 72 hours, but only because the errors were absurd enough to catch attention.17 The less visible cases are harder to count. In 2023, Hindawi retracted over 8,000 articles linked to paper mills and compromised peer review—more than all publishers combined had retracted in any previous year—and the cleanup cost its parent company Wiley the eventual discontinuation of the brand.18

These are not, primarily, stories about artificial intelligence. They are stories about institutions optimized for volume. A study of elite Chinese universities documented what the authors called the decoupling of daily research practice from ethical norms: national policymakers set vague aspirations for “world-class” status, university administrators translated these into ranking targets, deans passed them down as publication quotas, and junior researchers—facing a gap between what was demanded and what was possible—reported they had “no choice” but to falsify data or purchase authorship from paper mills.19 A separate survey found that more than half of Chinese medical residents admitted to some form of research misconduct.20 LLMs did not create what economists, with their penchant for meaning-destroying dimensionality reduction, would call science’s incentive “structure.” Rather this technology arrived into this context, offering a faster way to produce the artifacts the system rewards.

The logic didn’t stay contained in the academy. When Larry Page and Sergey Brin developed PageRank in the late 1990s, they drew explicitly on citation analysis. Their foundational paper cites Garfield alongside Pinski and Narin, whose influence-weighting method provided the recursive structure for the algorithm.21 Garfield’s solution to the problem of scientific information overload became Google’s solution to the problem of internet information overload, and it was gamed in the same ways. Search engine optimization is goal displacement with tighter feedback loops: the tools built to identify what mattered became tools to manufacture the appearance of mattering, and the manufacturing reshaped what got produced. The pattern Merton had diagnosed in bureaucracies, and worried about in science, became the organizing logic of the web.

What strikes me about the discourse around LLMs and science is that many critics have such bad intuitions about it—and they have bad intuitions because they’ve absorbed the perspective of the people they’re criticizing. The enthusiasts see a revolution, a fresh start for inquiry. The critics see a rupture, a collapse of standards. Enthusiasts see the technology as science’s salvation; critics see it as science’s undoing. Both agree that the technology is the agent; they disagree only about valence.

I don’t have a program for reform, but I also don’t think reform is possible unless we change the way we look at the problem. What I’ve tried to do here is make a different question askable—not whether LLMs can “do science” but how they get enrolled within a scientific system whose goals have already been displaced. The capabilities debate has been a way of not seeing the institutional context in which these tools arrive.

LLMs have context windows—the span of text they can attend to at once. It’s a telling reduction: “context” as buffer size, not a history, a situation, or a scene. The discourse around LLMs and science has its own context window, and it’s remarkably narrow. It sees the technology but not the institution; it debates capabilities while the enrollment is already underway. Like a typographical widow—a line stranded at the top of a new page, separated from the body that produced it—the institutional context has been cut off from its history, orphaned from the conversation, treated as background rather than foreground. LLMs didn’t create the dysfunction in scientific publishing; they inherited it, intensified it, made it run faster. Like a normally benign pathogen wreaking havoc in an immunocompromised patient, they point to the problem, but imagining them as the totality of the problem would be a deadly mistake.

They do the same for the web, which had been restructured by the same logic once PageRank exported Garfield’s citation analysis to organize the internet—and they generate paper-mill product and SEO content with equal facility because both are downstream of the same optimization, and their users are targeting isomorphic systems. One might hope that this acceleration heightens the contradictions, that the systems produce so much slop so quickly that the problem finally becomes undeniable. But, as we should all know by now, systems can persist in dysfunction indefinitely, and absurdity is not self-correcting. Whether the acceleration produces collapse or adaptation or simply more of the same is not a question about the technology, and it won’t be answered by debates about capabilities. It will be answered by the institutions that have been running this program for sixty years. Not, probably, by those who presently hold power within them—but by those who can build countervailing power, and who decide to change what gets measured, or finally wrench the institution of science itself from the false promise of measurement.

On enrollment in algorthmic contexts, see Angèle Christin, “The Ethnographer and the Algorithm,” Theory and Society (2020).

David A. Hollinger, “Free Enterprise and Free Inquiry: The Emergence of Laissez-Faire Communitarianism in the Ideology of Science in the United States,” New Literary History (1990).

Derek J. de Solla Price, Little Science, Big Science (1963). Price famously calculated that 80 to 90 percent of all the scientists who had ever lived were alive at the time of his writing, a statistic that illustrated the terrifying velocity of the “publication explosion.”

Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962).

Fritz Machlup, The Production and Distribution of Knowledge in the United States (1962).

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State (1998). Scott was synthesizing a tradition of institutional critique half a century old by the time Seeing Like a State appeared. That “legibility” has since become a skeleton key for so-called “rationalists” who stopped there is not the Scott’s fault—though it’s telling that a book about the dangers of simplification has itself been simplified into a vapid Silicon Valley slogan for today’s agents of simplification. I’m not sure if Scott would have appreciated the irony.

Eugene Garfield, “Citation Analysis as a Tool in Journal Evaluation,” Science (1972). On the history of ISI, see Alex Csiszar, “Gaming Metrics Before the Game,” in Gaming the Metrics: Misconduct and Manipulation in Academic Research, ed. Mario Biagioli and Alexandra Lippman (2020)

Robert K. Merton, “Bureaucratic Structure and Personality,” Social Forces 18, no. 4 (1940).

Csiszar, “Gaming Metrics Before the Game.”

quoted in Csiszar, “Gaming Metrics Before the Game.”

Harriet Zuckerman and Robert K. Merton, “Patterns of Evaluation in Science: Institutionalisation, Structure and Functions of the Referee System,” Minerva (1971). The warning, in footnote 18, reads: “Through the process of socially induced displacement of goals, this value of open communication would eventually become transformed for appreciable numbers of scholars and scientists into an urge to publish in periodicals, all apart from the worth of what was being submitted for publication. This development would in turn reinforce a concern within the community of scholars for the sifting, sorting and accrediting of manuscripts by some version of a referee-system.”

quoted in Csiszar, “Gaming Metrics Before the Game.”

Mary Douglas, How Institutions Think (1986).

Keith Hoskin, quoted in Csiszar, “Gaming Metrics Before the Game.”

On DORA, see the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (2012). On altmetrics, see Jason Priem et al., “Altmetrics: A Manifesto” (2010).

Wendy Nelson Espeland and Michael Sauder, Engines of Anxiety: Academic Rankings, Reputation, and Accountability (2016). Espeland and Sauder term this phenomenon “reactivity,” the process by which people or institutions change their behavior in response to being evaluated, eventually reshaping their own values to align with the metric. “Performativity” is also frequently used, but that term has been degraded by people (mostly whiny, reactionary pseuds) who use “performative” as a synonym for “insincere.”

Elisabeth Bik, “The Rat with the Big Balls and the Enormous Penis—How Frontiers Published a Paper with Botched AI-Generated Images,” Science Integrity Digest (2024).

“Hindawi Reveals Process for Retracting More Than 8,000 Paper Mill Articles,” Retraction Watch (2023).

Xinqu Zhang and Peng Wang, “Research Misconduct in China: Towards an Institutional Analysis,” Research Ethics (2025).

Lulin Chen et al., “Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices About Research Misconduct Among Medical Residents in Southwest China: A Cross-Sectional Study,” BMC Medical Education (2024).

Lawrence Page, Sergey Brin, Rajeev Motwani, and Terry Winograd, “The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web,” (1998). On the lineage from Garfield through Pinski and Narin, see Stephen J. Bensman, “Eugene Garfield, Francis Narin, and PageRank: The Theoretical Bases of the Google Search Engine,” (2013).

I wasn't aware with your game, sir. Great stuff.

This is excellent.